JavaScript Guides Advanced Mastering Ajax, Part 2: Make asynchronous

|

<script language="javascript" type="text/javascript"> var request = new XMLHttpRequest(); </script> |

That's not too hard, is it? Remember, JavaScript doesn't require typing on its variable, so you don't need anything

like you see in Listing 2 (which might be how you'd create this object in Java).

Listing 2. Java pseudo-code for creating XMLHttpRequest

XMLHttpRequest request = new XMLHttpRequest(); |

So you create a variable in JavaScript with var, give it a name (like "request"), and then assign it to a new instance

of XMLHttpRequest. At that point, you're ready to use the object in your functions.

In real life, things can go wrong and this code doesn't provide any error-handling. A slightly better approach is to

create this object and have it gracefully fail if something goes wrong. For example, many older browsers (believe it

or not, people are still using old versions of Netscape Navigator) don't support XMLHttpRequest and you need to

let those users know that something has gone wrong. Listing 3 shows how you might create this object so if

something fails, it throws out a JavaScript alert.

Listing 3. Create XMLHttpRequest with some error-handling abilities

<script language="javascript" type="text/javascript"> var request = false; try {

request = new XMLHttpRequest(); } catch (failed) {

request = false; } if (!request) alert("Error initializing XMLHttpRequest!");

</script> |

Make sure you understand each of these steps:

- Create a new variable called request and assign it a false value. You'll use false as a condition that means the XMLHttpRequest object hasn't been created yet.

- Add in a try/catch block:

- Try and create the XMLHttpRequest object.

- If that fails (catch (failed)), ensure that request is still set to false.

- Check and see if request is still false (if things are going okay, it won't be).

- If there was a problem (and request is false), use a JavaScript alert to tell users there was a problem.

This is pretty simple; it takes longer to read and write about than it does to actually understand for most JavaScript and Web developers. Now you've got an error-proof piece of code that creates an XMLHttpRequest object and even lets you know if something went wrong.

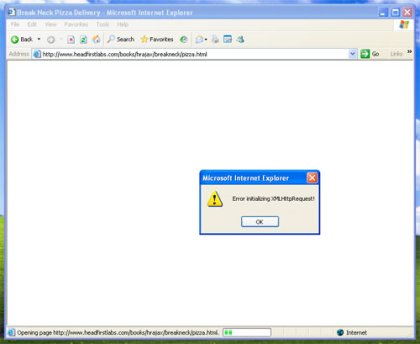

This all looks pretty good ... at least until you try this code in Internet Explorer. If you do, you're going to get something that looks an awful lot like Figure 1.

Figure 1. Internet Explorer reporting an error

Clearly, something isn't working; Internet Explorer is hardly an out-of-date browser and about 70 percent of the world uses Internet Explorer. In other words, you won't do well in the Web world if you don't support Microsoft and Internet Explorer! So, you need a different approach to deal with Microsoft's browsers.

It turns out that Microsoft supports Ajax, but calls its version of XMLHttpRequest something different. In fact, it calls it several different things. If you're using a newer version of Internet Explorer, you need to use an object called Msxml2.XMLHTTP; some older versions of Internet Explorer use Microsoft.XMLHTTP. You need to support these two object types (without losing the support you already have for non-Microsoft browsers). Check out Listing 4 which adds Microsoft support to the code you've already seen.

Listing 4. Add support for Microsoft browsers

<script language="javascript" type="text/javascript"> var request = false; try {

request = new XMLHttpRequest(); } catch (trymicrosoft) {

try {

request = new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP");

} catch (othermicrosoft) {

try {

request = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

} catch (failed) {

request = false; } } } if (!request) alert("Error initializing XMLHttpRequest!");

</script> |

It's easy to get lost in the curly braces, so I'll walk you through this one step at a time:

- Create a new variable called request and assign it a false value. Use false as a condition that means the XMLHttpRequest object isn't created yet.

- Add in a try/catch block:

- Try and create the XMLHttpRequest object.

- If that fails (catch (trymicrosoft)):

- Try and create a Microsoft-compatible object using the newer versions of Microsoft (Msxml2.XMLHTTP).

- If that fails (catch (othermicrosoft)), try and create a Microsoft-compatible object using the older versions of Microsoft (Microsoft.XMLHTTP).

- If that fails (catch (failed)), ensure that request is still set to false.

- Check and see if request is still false (if things are okay, it won't be).

- If there was a problem (and request is false), use a JavaScript alert to tell users there was a problem.

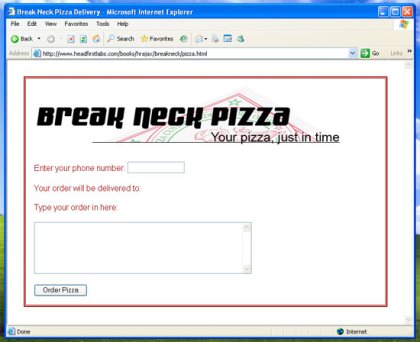

Make these changes to your code and try things out in Internet Explorer again; you should see the form you created (without an error message). In my case, that results in something like Figure 2.

Figure 2. Internet Explorer working normally

Take a look back at Listings 1, 3, and 4 and notice that all of this code is nested directly within script tags. When JavaScript is coded like that and not put within a method or function body, it's called static JavaScript. This means that the code is run sometime before the page is displayed to the user. (It's not 100 percent clear from the specification precisely when this code runs and browsers do things differently; still, you're guaranteed that the code is run before users can interact with your page.) That's usually how most Ajax programmers create the XMLHttpRequest object.

That said, you certainly can put this code into a method as shown in Listing 5.

Listing 5. Move XMLHttpRequest creation code into a method

<script language="javascript" type="text/javascript"> var request; function createRequest() {

try {

request = new XMLHttpRequest(); } catch (trymicrosoft) {

try {

request = new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP");

} catch (othermicrosoft) {

try {

request = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

} catch (failed) {

request = false; } } } if (!request) alert("Error initializing XMLHttpRequest!");

} </script> |

With code setup like this, you'll need to call this method before you do any Ajax work. So you might have something like Listing 6.

Listing 6. Use an XMLHttpRequest creation method

<script language="javascript" type="text/javascript"> var request; function createRequest() {

try {

request = new XMLHttpRequest(); } catch (trymicrosoft) {

try {

request = new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP");

} catch (othermicrosoft) {

try {

request = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

} catch (failed) {

request = false; } } } if (!request) alert("Error initializing XMLHttpRequest!");

} function getCustomerInfo() {

createRequest(); // Do something with the request variable } </script> |

The only concern with this code -- and the reason most Ajax programmers don't use this approach -- is that it delays error notification. Suppose you have a complex form with 10 or 15 fields, selection boxes, and the like, and you fire off some Ajax code when the user enters text in field 14 (way down the form). At that point, getCustomerInfo() runs, tries to create an XMLHttpRequest object, and (for this example) fails. Then an alert is spit out to the user, telling them (in so many words) that they can't use this application. But the user has already spent time entering data in the form! That's pretty annoying and annoyance is not something that typically entices users back to your site.

In the case where you use static JavaScript, the user is going to get an error as soon as they hit your page. Is that also annoying? Perhaps; it could make users mad that your Web application won't run on their browser. However, it's certainly better than spitting out that same error after they've spent 10 minutes entering information. For that reason alone, I encourage you to set up your code statically and let users know early on about possible problems.

Sending requests with XMLHttpRequest

Once you have your request object, you can begin the request/response cycle. Remember, XMLHttpRequest's only purpose is to allow you to make requests and receive responses. Everything else -- changing the user interface, swapping out images, even interpreting the data that the server sends back -- is the job of JavaScript, CSS, or other code in your pages. With XMLHttpRequest ready for use, now you can make a request to a server.

Ajax has a sandbox security model. As a result, your Ajax code (and specifically, the XMLHttpRequest object) can only make requests to the same domain on which it's running. You'll learn lots more about security and Ajax in an upcoming article, but for now realize that code running on your local machine can only make requests to server-side scripts on your local machine. If you have Ajax code running on www.breakneckpizza.com, it must make requests to scripts that run on www.breakneckpizza.com.

The first thing you need to determine is the URL of the server to connect to. This isn't specific to Ajax -- obviously you should know how to construct a URL by now -- but is still essential to making a connection. In most applications, you'll construct this URL from some set of static data combined with data from the form your users work with. For example, Listing 7 shows some JavaScript that grabs the value of the phone number field and then constructs a URL using that data.

Listing 7. Build a request URL

<script language="javascript" type="text/javascript"> var request = false; try {

request = new XMLHttpRequest(); } catch (trymicrosoft) {

try {

request = new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP");

} catch (othermicrosoft) {

try {

request = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

} catch (failed) {

request = false; } } } if (!request) alert("Error initializing XMLHttpRequest!");

function getCustomerInfo() {

var phone = document.getElementById("phone").value;

var url = "/cgi_local/lookupCustomer_phone_.html" + escape(phone); } </script> |

Nothing here should trip you up. First, the code creates a new variable named phone and assigns the value of the form field with an ID of "phone." Listing 8 shows the XHTML for this particular form in which you can see the phone field and its id attribute.

Listing 8. The Break Neck Pizza form

<body> <p><img src="/breakneck_logo_4c.gif" alt="Break Neck Pizza" /></p> <form action="POST"> <p>Enter your phone number: <input type="text" size="14" name="phone" id="phone" onChange="getCustomerInfo();" /> </p> <p>Your order will be delivered to:</p> <div id="address"></div> <p>Type your order in here:</p> <p><textarea name="order" rows="6" cols="50" id="order"></textarea></p> <p><input type="submit" value="Order Pizza" id="submit" /></p> </form> </body> |

Also notice that when users enter their phone number or change the number, it fires off the getCustomerInfo() method shown in Listing 8. That method then grabs the number and uses it to construct a URL string stored in the url variable. Remember: Since Ajax code is sandboxed and can only connect to the same domain, you really shouldn't need a domain name in your URL. In this example, the script name is /cgi-local/lookupCustomer.php. Finally, the phone number is appended to this script as a GET parameter: "phone=" + escape(phone).

If you've never seen the escape() method before, it's used to escape any characters that can't be sent as clear text correctly. For example, any spaces in the phone number are converted to %20 characters, making it possible to pass the characters along in the URL.

You can add as many parameters as you need. For example, if you wanted to add another parameter, just append it onto the URL and separate parameters with the ampersand (&) character [the first parameter is separated from the script name with a question mark (?)].

With a URL to connect to, you can configure the request. You'll accomplish this using the open() method on your XMLHttpRequest object. This method takes as many as five parameters:

- request-type: The type of request to send. Typical values are GET or POST, but you can also send HEAD requests.

- url: The URL to connect to.

- asynch: True if you want the request to be asynchronous and false if it should be a synchronous request. This parameter is optional and defaults to true.

- username: If authentication is required, you can specify the username here. This is an optional parameter and has no default value.

- password: If authentication is required, you can specify the password here. This is an optional parameter and has no default value.

Typically, you'll use the first three of these. In fact, even when you want an asynchronous request, you should specify "true" as the third parameter. That's the default setting, but it's a nice bit of self-documentation to always indicate if the request is asynchronous or not.

Put it all together and you usually end up with a line that looks a lot like Listing 9.

function getCustomerInfo() {

var phone = document.getElementById("phone").value;

var url = "/cgi_local/lookupCustomer_phone_.html" + escape(phone); request.open("GET", url, true);

} |

Once you have the URL figured out, then this is pretty trivial. For most requests, using GET is sufficient (you'll see the situations in which you might want to use POST in future articles); that, along with the URL, is all you need to use open().

In a later article in this series, I'll spend significant time on writing and using asynchronous code, but you should get an idea of why that last parameter in open() is so important. In a normal request/response model -- think Web 1.0 here -- the client (your browser or the code running on your local machine) makes a request to the server. That request is synchronous; in other words, the client waits for a response from the server. While the client is waiting, you usually get at least one of several forms of notification that you're waiting:

- An hourglass (especially on Windows).

- A spinning beachball (usually on Mac machines).

- The application essentially freezes and sometimes the cursor changes.

This is what makes Web applications in particular feel clunky or slow -- the lack of real interactivity. When you push a button, your application essentially becomes unusable until the request you just triggered is responded to. If you've made a request that requires extensive server processing, that wait might be significant (at least for today's multi-processor, DSL, no-waiting world).

An asynchronous request though, does not wait for the server to respond. You send a request and then your application continues on. Users can still enter data in a Web form, click other buttons, even leave the form. There's no spinning beachball or whirling hourglass and no big application freeze. The server quietly responds to the request and when it's finished, it let's the original requestor know that it's done (in ways you'll see in just a moment). The end result is an application that doesn't feel clunky or slow, but instead is responsive, interactive, and feels faster. This is just one component of Web 2.0, but it's a very important one. All the slick GUI components and Web design paradigms can't overcome a slow, synchronous request/response model.

Once you configure the request with open(), you're ready to send the request. Fortunately, the method for sending a request is named more properly than open(); it's simply called send().

send() takes only a single parameter, the content to send. But before you think too much on that, recall that you are already sending data through the URL itself:

var url = "/cgi_local/lookupCustomer_phone_.html" + escape(phone); |

Although you can send data using send(), you can also send data through the URL itself. In fact, in GET requests (which will constitute as much as 80 percent of your typical Ajax usage), it's much easier to send data in the URL. When you start to send secure information or XML, then you want to look at sending content through send() (I'll discuss both secure data and XML messaging in a later article in this series). When you don't need to pass data along through send(), then just pass null as the argument to this method. So, to send a request in the example you've seen throughout this article, that's exactly what is needed (see Listing 10).

function getCustomerInfo() {

var phone = document.getElementById("phone").value;

var url = "/cgi_local/lookupCustomer_phone_.html" + escape(phone); request.open("GET", url, true);

request.send(null); } |

At this point, you've done very little that feels new, revolutionary, or asynchronous. Granted, that little keyword "true" in the open() method sets up an asynchronous request. But other than that, this code resembles programming with Java servlets and JSPs, PHP, or Perl. So what's the big secret to Ajax and Web 2.0? The secret revolves around a simple property of XMLHttpRequest called onreadystatechange.

First, be sure you understand the process that you created in this code (review Listing 10 if you need to). A request is set up and then made. Additionally, because this is a synchronous request, the JavaScript method (getCustomerInfo() in the example) will not wait for the server. So the code will continue; in this case, that means that the method will exit and control will return to the form. Users can keep entering information and the application isn't going to wait on the server.

This creates an interesting question, though: What happens when the server has finished processing the request? The answer, at least as the code stands right now, is nothing! Obviously, that's not good, so the server needs to have some type of instruction on what to do when it's finished processing the request sent to it by XMLHttpRequest.

This is where that onreadystatechange property comes into play. This property allows you to specify a callback method. A callback allows the server to (can you guess?) call back into your Web page's code. It gives a degree of control to the server, as well; when the server finishes a request, it looks in the XMLHttpRequest object and specifically at the onreadystatechange property. Whatever method is specified by that property is then invoked. It's a callback because the server initiates calling back into the Web page -- regardless of what is going in the Web page itself. For example, it might call this method while the user is sitting in her chair, not touching the keyboard; however, it might also call the method while the user is typing, moving the mouse, scrolling, clicking a button ... it doesn't matter what the user is doing.

This is actually where the asynchronicity comes into play: The user operates the form on one level while on another level, the server answers a request and then fires off the callback method indicated by the onreadystatechange property. So you need to specify that method in your code as shown in Listing 11.

Listing 11. Set a callback method

function getCustomerInfo() {

var phone = document.getElementById("phone").value;

var url = "/cgi_local/lookupCustomer_phone_.html" + escape(phone); request.open("GET", url, true);

request.onreadystatechange = updatePage; request.send(null); } |

Pay close attention to where in the code this property is set -- it's before send() is called. You must set this property before the request is sent, so the server can look up the property when it finishes answering a request. All that's left now is to code the updatePage() which is the focus of the last section in this article.

You made your request, your user is happily working in the Web form (while the server handles the request), and now the server finishes up handling the request. The server looks at the onreadystatechange property and figures out what method to call. Once that occurs, you can think of your application as any other app, asynchronous or not. In other words, you don't have to take any special action writing methods that respond to the server; just change the form, take the user to another URL, or do whatever else you need to in response to the server. In this section, we'll focus on responding to the server and then taking a typical action -- changing on the fly part of the form the user sees.

You've already seen how to let the server know what to do when it's finished: Set the onreadystatechange property of the XMLHttpRequest object to the name of the function to run. Then, when the server has processed the request, it will automatically call that function. You also don't need to worry about any parameters to that method. You'll start with a simple method like in Listing 12.

Listing 12. Code the callback method

<script language="javascript" type="text/javascript"> var request = false; try {

request = new XMLHttpRequest(); } catch (trymicrosoft) {

try {

request = new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP");

} catch (othermicrosoft) {

try {

request = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

} catch (failed) {

request = false; } } } if (!request) alert("Error initializing XMLHttpRequest!");

function getCustomerInfo() {

var phone = document.getElementById("phone").value;

var url = "/cgi_local/lookupCustomer_phone_.html" + escape(phone); request.open("GET", url, true);

request.onreadystatechange = updatePage; request.send(null); } function updatePage() {

alert("Server is done!");

} </script> |

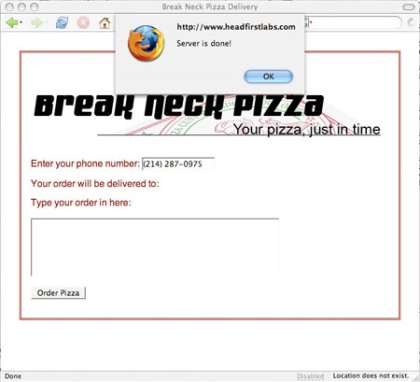

This just spits out a handy alert, to tell you when the server is done. Try this code in your own page, save the page, and then pull it up in a browser (if you want the XHTML from this example, refer back to Listing 8). When you enter in a phone number and leave the field, you should see the alert pop up (see Figure 3); but click OK and it pops up again ... and again.

Figure 3. Ajax code popping up an alert

Depending on your browser, you'll get two, three, or even four alerts before the form stops popping up alerts. So what's going on? It turns out that you haven't taken into account the HTTP ready state, an important component of the request/response cycle.

Earlier, I said that the server, once finished with a request, looks up what method to call in the onreadystatechange property of XMLHttpRequest. That's true, but it's not the whole truth. In fact, it calls that method every time the HTTP ready state changes. So what does that mean? Well, you've got to understand HTTP ready states first.

An HTTP ready state indicates the state or status of a request. It's used to figure out if a request has been started, if it's being answered, or if the request/response model has completed. It's also helpful in determining whether it's safe to read whatever response text or data that a server might have supplied. You need to know about five ready states in your Ajax applications:

- 0: The request is uninitialized (before you've called open()).

- 1: The request is set up, but hasn't been sent (before you've called send()).

- 2: The request was sent and is being processed (you can usually get content headers from the response at this point).

- 3: The request is being processed; often some partial data is available from the response, but the server hasn't finished with its response.

- 4: The response is complete; you can get the server's response and use it.

As with almost all cross-browser issues, these ready states are used somewhat inconsistently. You might expect to always see the ready state move from 0 to 1 to 2 to 3 to 4, but in practice, that's rarely the case. Some browsers never report 0 or 1 and jump straight to 2, then 3, and then 4. Other browsers report all states. Still others will report ready state 1 multiple times. As you saw in the last section, the server called updatePage() several times and each invocation resulted in an alert box popping up -- probably not what you intended!

For Ajax programming, the only state you need to deal with directly is ready state 4, indicating that a server's response is complete and it's safe to check the response data and use it. To account for this, the first line in your callback method should be as shown in Listing 13.

Listing 13. Check the ready state

function updatePage() {

if (request.readyState == 4) alert("Server is done!");

} |

This change checks to ensure that the server really is finished with the process. Try running this version of the Ajax code and you should only get the alert message one time, which is as it should be.

Despite the apparent success of the code in Listing 13, there's still a problem -- what if the server responds to your request and finishes processing, but reports an error? Remember, your server-side code should care if it's being called by Ajax, a JSP, a regular HTML form, or any other type of code; it only has the traditional Web-specific methods of reporting information. And in the Web world, HTTP codes can deal with the various things that might happen in a request.

For example, you've certainly entered a request for a URL, typed the URL incorrectly, and received a 404 error code to indicate a page is missing. This is just one of many status codes that HTTP requests can receive as a status. 403 and 401, both indicating secure or forbidden data being accessed, are also common. In each of these cases, these are codes that result from a completed response. In other words, the server fulfilled the request (meaning the HTTP ready state is 4), but is probably not returning the data expected by the client.

In addition to the ready state then, you also need to check the HTTP status. You're looking for a status code of 200 which simply means okay. With a ready state of 4 and a status code of 200, you're ready to process the server's data and that data should be what you asked for (and not an error or other problematic piece of information). Add another status check to your callback method as shown in Listing 14.

Listing 14. Check the HTTP status code

function updatePage() {

if (request.readyState == 4) if (request.status == 200) alert("Server is done!");

} |

To add more robust error handling -- with minimal complication -- you might add a check or two for other status codes; check out the modified version of updatePage() in Listing 15.

Listing 15. Add some light error checking

function updatePage() {

if (request.readyState == 4) if (request.status == 200) alert("Server is done!");

else if (request.status == 404) alert("Request URL does not exist");

else alert("Error: status code is " + request.status);

} |

Now change the URL in your getCustomerInfo() to a non-existent URL and see what happens. You should see an alert that tells you the URL you asked for doesn't exist -- perfect! This is hardly going to handle every error condition, but it's a simple change that covers 80 percent of the problems that can occur in a typical Web application.

Now that you made sure the request was completely processed (through the ready state) and the server gave you a normal, okay response (through the status code), you can finally deal with the data sent back by the server. This is conveniently stored in the responseText property of the XMLHttpRequest object.

Details about what the text in responseText looks like, in terms of format or length, is left intentionally vague. This allows the server to set this text to virtually anything. For instance, one script might return comma-separated values, another pipe-separated values (the pipe is the | character), and another may return one long string of text. It's all up to the server.

In the case of the example used in this article, the server returns a customer's last order and then their address, separated by the pipe symbol. The order and address are both then used to set values of elements on the form; Listing 16 shows the code that updates the display.

Listing 16. Deal with the server's response

function updatePage() {

if (request.readyState == 4) {

if (request.status == 200) {

var response = request.responseText.split("|");

document.getElementById("order").value = response[0];

document.getElementById("address").innerHTML =

response[1].replace(/\n/g, " } else alert("status is " + request.status);

} } |

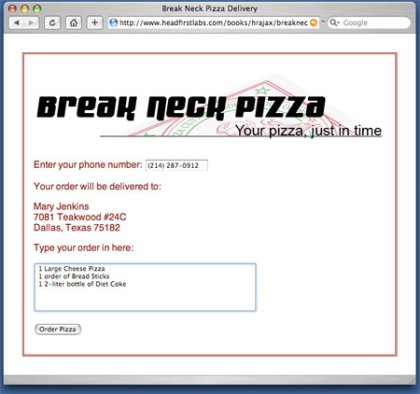

First, the responseText is pulled and split on the pipe symbol using the JavaScript split() method. The resulting array of values is dropped into response. The first value -- the customer's last order -- is accessed in the array as response[0] and is set as the value of the field with an ID of "order." The second value in the array, at response[1], is the customer's address and it takes a little more processing. Since the lines in the address are separated by normal line separators (the "\n" character), the code needs to replace these with XHTML-style line separators, <br />s. That's accomplished through the use of the replace() function along with a regular expression. Finally, the modified text is set as the inner HTML of a div in the HTML form. The result is that the form suddenly is updated with the customer's information, as you can see in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The Break Neck form after it retrieves customer data

Before I wrap up, another important property of XMLHttpRequest is called responseXML. That property contains (can you guess?) an XML response in the event that the server chooses to respond with XML. Dealing with an XML response is quite different than dealing with plain text and involves parsing, the Document Object Model (DOM), and several other considerations. You'll learn more about XML in a future article. Still, because responseXML commonly comes up in discussions surrounding responseText, it's worth mentioning here. For many simple Ajax applications, responseText is all you need, but you'll soon learn about dealing with XML through Ajax applications as well.

In conclusion

You might be a little tired of XMLHttpRequest -- I rarely read an entire article about a single object, especially one that is this simple. However, you will use this object over and over again in each page and application that you write that uses Ajax. Truth be told, there's quite a bit still to be said about XMLHttpRequest. In coming articles, you'll learn to use POST in addition to GET in your requests, set and read content headers in your request as well as the response from the server; you'll understand how to encode your requests and even handle XML in your request/response model.

Quite a bit further down the line, you'll also see some of the popular Ajax toolkits that are available. These toolkits actually abstract away most of the details discussed in this article and make Ajax programming easier. You might even wonder why you have to code all this low-level detail when toolkits are so readily available. The answer is, it's awfully hard to figure out what goes wrong in your application if you don't understand what is going on in your application.

So don't ignore these details or speed through them; when your handy-dandy toolkit creates an error, you won't be stuck scratching your head and sending an email to support. With an understanding of how to use XMLHttpRequest directly, you'll find it easy to debug and fix even the strangest problems. Toolkits are fine unless you count on them to take care of all your problems.

So get comfortable with XMLHttpRequest. In fact, if you have Ajax code running that uses a toolkit, try to rewrite it using just the XMLHttpRequest object and its properties and methods. It will be a great exercise and probably help you understand what's going on a lot better.

In the next article, you'll dig even deeper into this object, exploring some of its tricker properties (like responseXML), as well as how to use POST requests and send data in several different formats. So start coding and check back here in about a month.

___________

Re-printed from http://www-128.ibm.com/developerworks/web/library/wa-ajaxintro1.htm with permission.

First published by IBM developerWorks at http://www.ibm.com/developerWorks/

—

JavaScripts Guides: Beginner, Advanced

JavaScripts Tutorials: Beginner, Advanced

[Home] [Templates] [Blog] [Forum] [Directory] JavaScript Guides Advanced -

Mastering Ajax Part 2 Make asynchronous requests with JavaScript and Ajax